Oli Dugmore 4am - 7am

26 September 2023, 08:42

This week I am going to head 'off-piste' into the political jungle of UK politics and how the chasms of differences of opinion within each of the main political parties over nearly seventy years have eventually brought the public's support for each of them in turn to a grinding halt.

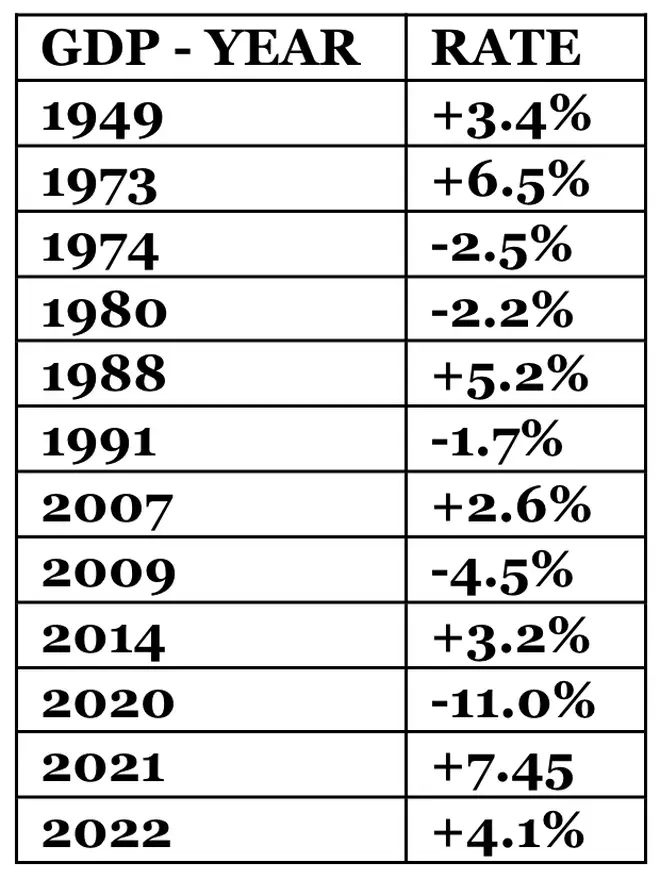

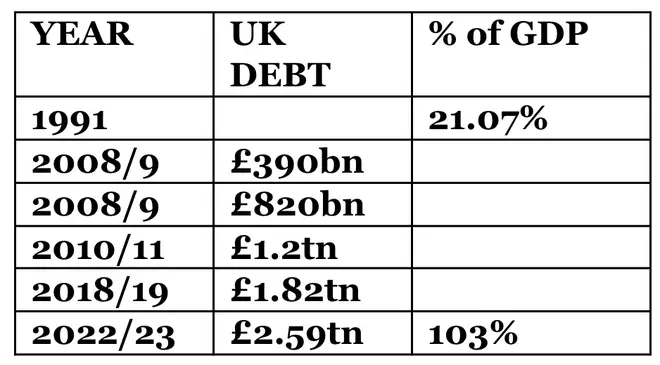

A combination of world events, gargantuan global financial imponderables, political incompetence, and the divisions within those ruling parties/governments have severely damaged the UK's gross domestic product during this period, as well as catapulting public sector borrowing to unsustainable levels.

The 'end' result normally sees the government of the day being shown the door by the democratic electoral process.

There has been a litany of catastrophic events that have changed the demographics of the political scene here since WW2. Regardless of anyone's political persuasion, Clement Attlee's Labour Government was good for the country in 1946 in terms of the introduction of Bevan's NHS, which proved to be the cornerstone of a decently operated public sector.

That said, future Labour Governments had great difficulty in understanding that a buoyant private sector is a prerequisite for generating tax revenue to sustain a large public sector that has increased and multiplied over the years.

It's not egregious to make money and to generate wealth. It is straightforward common sense. It's fair to say that Blair and Mandelson eventually 'grasped the nettle' quite quickly in 1997.

Sir Winston Churchill defeated Attlee in 1951 and was Prime Minister until 1955. He was 81 years of age when he handed over to Sir Anthony Eden. Eden's handling of the Suez crisis was a disaster. He was succeeded by Harold Macmillan, who muddled through until 1963. Macmillan's government was rocked by the Vassall and Profumo affairs and Macmillan decided to step down in October 1963, citing ill health.

He was replaced as Prime Minister by Sir Alec Douglas-Home, but the Conservatives were defeated in the 1964 general election by Harold Wilson's administration. Harold Wilson made it clear that he especially enjoyed his first term in office when his majority was wafer-thin.

It was then he felt that the dissenters in his party would be forced to toe the party line and thus keep their powder dry. His second administration between 1974-1976 again with a majority of three proved to be a bridge too far when the IMF were forced to take a vice-like grip on the country's finances, resulting in the bank rate hitting 9% in the fight against inflation.

Set out below are two charts - one for GDP and one for UK Public Sector Borrowing. I hope they illustrate some points I will be highlighting about how damaging divisions in political parties and governments can be for the UK's economy, resulting in the public's disenchantment.

There was a litany of mistakes from virtually all governments following Wilson. Ironically, Wilson's defeat in 1970 was the most surprising, especially as the country did not appear to be in the mood for an Edward Heath - "Cassandra prophesying doom" operation - nor did the electorate want Heath's reconstructed, reactionary Toryism of free enterprise and anti-trade unionism at that time.

The Heath Government's demise in 1974 was down to two catastrophic issues of the day - the "boom and bust" policies of the reckless Chancellor Anthony Barber, which saw inflation up to 21%, that eventually saw the Conservatives thrown out of office.

From 1976, Labour's James Callaghan had "the winter of discontent" to contend with, as well as the Lib-Lab pact which irritated the public at large.

They contributed to the demise of his government. Thatcher proved to be a breath of spring air, with that indomitable spirit that was infectious, taking the country through the Falklands war at a time she was very unpopular.

Her innovative tax policies against a background of high inflation resulting in interest rates of 17% in 1979 and unemployment reaching an eye-watering 11.7 million in 1984 saw a surprising resurgence of the economy.

Eventually, the Conservatives started to see splits appearing, with Michael Heseltine seemingly triggering her removal from office in 1990 as she became increasingly unpopular by her draconian approach to politics.

Needless to say, on the international stage, Thatcher was a star performer with the considerable help of Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev.

Sir John Major, post the 1992 election when he surprisingly defeated Neil Kinnock, left him with a small majority and significant infighting within the Government - "those bastards" as he referred to them! Unfortunately for John Major, Britain was forced to leave the ERM (Exchange Rate Mechanism) in 1992, less than two years after joining. This day became known as 'Black Wednesday', costing the UK Treasury £3.3 billion, with rates being jacked up to 15%.

That fiasco, Tory sleaze and 18 years of Tory rule saw Tony Blair elected by a massive majority in 1997. It should not be forgotten that the Conservative Chancellor Ken Clarke left the economy in great shape.

I won't delve too heavily into the past 25 years, as people's memories are much clearer. Tony Blair initially did well and was disciplined, but an air of arrogance and overconfidence grew uneasily in his government.

It was the Iraq war that saw Blair's popularity rapidly diminish, coupled with his obsession over membership of the EU and for the UK to join the Euro.

There is no doubt that the banking crisis, the worst financial downturn since the 1929 crash due to soft regulation and poor credit assessment by the banks, eventually put Gordon Brown's premiership to the sword. Had he called a snap election in 2009, many feel he would have won.

The Conservative-Lib Dem coalition of 2015 was initially quite successful in restoring fiscal confidence under George Osborne as Chancellor. However, after the 2015 General Election, austerity took its toll. It was thought to have been overplayed, though the Conservatives had inherited a frightening financial shortfall.

That issue, together with massive infighting over the BREXIT referendum, which was very badly orchestrated, saw David Cameron resign.

Theresa May's problems were insurmountable. She did not really believe in BREXIT.

Hard though she tried, the Government and party were split in sunder, not helped by the fact that Parliament refused to deliver the democratic decision of the country.

Boris Johnson's uncoordinated efforts, severely interrupted and damaged by Covid and Liz Truss's poorly presented plans for growth are well chronicled by better observers than me.

Suffice to say that PM Sunak's Herculean task of putting 'Humpty' together again will need a miracle to succeed. However, the same theme prevails and has done so for over 75 years.

World events are challenging enough for any government.

However, governments and parties that are irrevocably split are the cause of significant economic damage to the country.