Paul Brand 10am - 12pm

31 December 2019, 09:00

As the world waves goodbye to the 2010s and we prepare ourselves for the 2020s, LBC News looks back at a tumultuous decade in British politics.

The UK has experienced a number of chaotic decades over the past 100 years, a number of which have turned the country and its politics on its head.

From a declining empire at the beginning of the 20th century, to a rapidly growing population at the beginning of the 21st, dividing our history into decades has always been an appealing but simple way of reflecting upon our history.

Whether it was recovering from the First World War in the 1920s, gearing the country's economy towards the Second World War in the early 1940s, battling with unemployment throughout the 1970s, or Margaret Thatcher's sheer dominance during the 1980s - all of the above have shaken the UK to its political core.

As we welcomed in the new millennium, Tony Blair was just over halfway through his first tenure as prime minister after the New Labour landslide.

He survived two more general elections throughout the decade and his party would not relinquish the reins of power for the rest of the noughties.

But then came the decade with no proper nickname - the 2010s? The teenies? Or just the tens?

Whatever you call them, they have been some of the most fraught and divisive years in the recent history of our nation.

They have given us four prime ministers, four referenda and the most fractious topic in UK politics for years - Brexit.

The first year of the teenies saw two dynasties changing hands.

Gordon Brown's Labour, in power since 1997, handed No 10 to the Conservative Party's David Cameron.

However, the Tory leader needed a helping hand from the Lib Dems' Nick Clegg, who stepped in as deputy prime minister following a wave of "Cleggmania".

This unlikely government became known as "The Coalition" and, to the surprise of many, survived until 2015 under the rules of the brand new Fixed-term Parliaments Act.

It was a partnership that would eventually erode the public's trust in the Liberal Democrats for the rest of the decade and they have still not fully recovered - just ask anyone under the age of 26 about student loans and you will understand why.

We could have predicted the knock-on effect of the Lib Dems "jumping into bed" with the Tories, but what we could not have foreseen was the impact this one election would have over the next ten years.

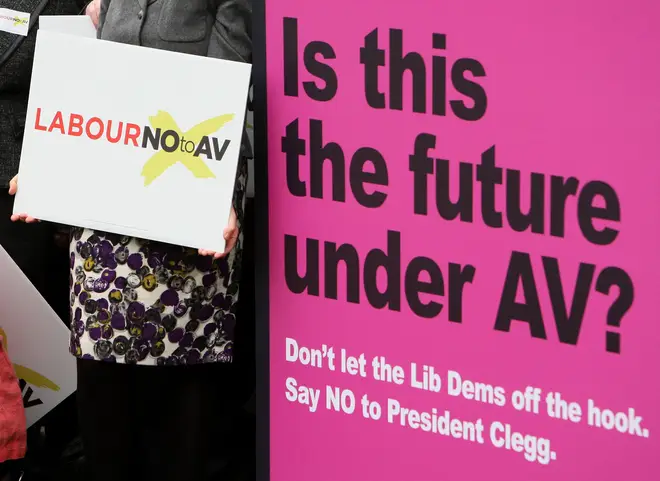

In 2011, David Cameron unleashed the first two of the decade's four referenda on the UK - a ballot on the devolution of powers to the Welsh Assembly and a referendum to overhaul the First Past the Post voting system.

Wales voted overwhelmingly in favour of making their own laws, and the UK firmly rejected the Alternative Vote method, a move that has haunted smaller political parties since.

However, neither ballots experienced high turnouts, with both failing to persuade any more than 43 per cent of the respective electorates to head to the polling stations.

The following year gave us cause for celebration with the Queen's Diamond Jubilee and the 2012 London Olympics.

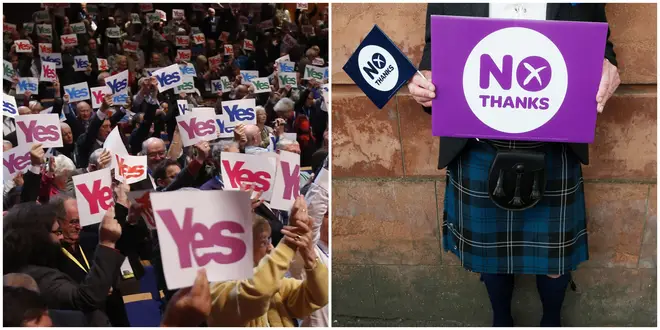

However, it also saw the start of a somewhat bitter campaign over Scotland's potential independence from the rest of the United Kingdom.

Earlier in the year, we witnessed the formation of the pro-Union "Better Together" campaign and the pro-Independence "Yes Scotland" organisation.

As 2012 progressed, the Edinburgh Agreement passed in October, which laid out the terms of the 2014 referendum.

The future Prime Minister Boris Johnson also won a second term as London Mayor in May, narrowly beating Labour's Ken Livingstone.

Long before Brexit had begun dominating the airwaves, newspapers and general public discourse, the UK Parliament drew up a private member's bill in a bid to ensure Britain held a referendum on its membership of the European Union.

Despite a number of readings in the Commons and the Lords, the bill failed to pass into legislation.

However, it laid the foundations of a subsequent, similar bill with the same objective a couple of years later - which set the wheels in motion for Brexit.

Elsewhere, Margaret Thatcher's death in April polarised the country. The former prime minister was given a ceremonial funeral, much to the dismay of those who disliked her who celebrated her passing at street parties across the UK.

And in the summer of 2013, the Home Office was criticised for its "Go Home" vans campaign that formed part of the hostile environment policy - something the then Ukip leader Nigel Farage described as "unpleasant".

The political landscape in Britain truly started shifting in 2014.

Local elections were held at the same time as the European elections in May, which saw the birth of a soon-to-be political frontrunner - Nigel Farage.

Ukip came along and blew the Tories and Labour out of the water with an unprecedented European election win, which saw the issue of leaving the European Union move to the forefront of British politics.

The party's impact was so strong that Douglas Carswell was soon elected as their first MP following a Clacton by-election in August.

Mark Reckless soon joined his Ukip colleague in the Commons after winning the Rochester and Strood by-election in November.

But the biggest event of the year came in September when Scotland narrowly voted to remain in the United Kingdom, with 55 per cent of the country voting for the Union and almost 45 per cent voting against.

Despite the result, the Scottish National Party would go on to become the dominant force in Scottish politics for the rest of the decade and the issue of independence remains far from settled to this day.

In 2015, the UK headed to the ballot box for what was supposed to be the last occasion of the decade, under the rules stipulated by the Fixed-term Parliaments Act.

David Cameron blew away his opponents and won a surprise majority in the Commons - despite the intervention of Russell Brand and #Milifandom - giving the Conservatives their first majority since 1992 and bringing an end to the Coalition.

Nick Clegg's Liberal Democrats lost 49 of their 57 seats, whereas the newly-appointed SNP leader - Nicola Sturgeon - saw her party's stock rise dramatically, as they won an additional 50 seats on top of their formerly humble six.

In light of the result, Nick Clegg and Ed Miliband stepped down as party chiefs to be replaced by Tim Farron and Jeremy Corbyn respectively.

The fate of the two new leaders would ultimately end up the same, but the effect Mr Corbyn would prove to have on the Labour Party would be momentous.

Part of David Cameron's election promise was to hold a referendum on leaving the EU and, as such, the Tory Party saw its European Union Referendum Act granted Royal Assent by the end of the year.

2016 was quite simply the year of Brexit. In February, David Cameron confirmed the UK would hold a referendum on its membership of the European Union, which would take place on 23 June.

Experts, polls and pundits alike largely predicted that the status quo would be maintained and that the UK would stay in the EU.

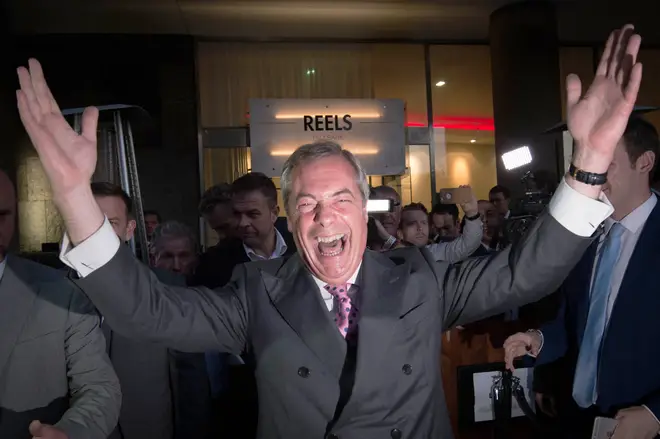

However, once polls closed and the results began filtering in, it became clear that the UK would in fact be leaving.

In the end, almost 52 per cent voted to Leave and just over 48 per cent voted to Remain.

Nigel Farage declared the 23 June as the UK's "Independence Day" and tears of both joy and despair were shed on either side of the campaign trail.

The result has dominated British politics since but, upon writing at the end of December 2019, has still not been implemented.

David Cameron felt he could no longer lead his party or the country after the vote, having passionately campaigned for Remain. Shortly after, he handed in his resignation.

Mr Cameron was replaced by Theresa May later in the year, following a leadership election plagued by infighting and withdrawals.

Elsewhere, Jeremy Corbyn faced a challenge to his reign as Labour chief but convincingly saw off his rival, Owen Smith.

Theresa May became just the second female prime minister in the history of the UK upon her appointment in 2016, but in 2017 she sought to obtain a greater majority - much like her predecessor Margaret Thatcher - than what she inherited from David Cameron.

In April, she saw legislation for a snap election sail through the Commons with the new prime minister saying she hoped to secure a larger majority to "strengthen [her] hand" in the upcoming Brexit negotiations - initiated by the triggering of Article 50 on 29 March that year.

However, on 8 June, Mrs May saw her slim majority shatter in front of her eyes, losing 13 vital seats. Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party won an extra 30, creating a Hung Parliament that became plagued by attrition and stalemate.

The Tory leader held on to power, but only thanks to a confidence and supply arrangement with Arlene Foster's DUP in Northern Ireland, who became one of the most influential players in British politics over the next two years.

Tim Farron stepped down as Lib Dem leader after his party's performance at the polls and was replaced by an unopposed Vince Cable.

On 19 June, the first round of UK-EU exit negotiations begun and in September the prime minister delivered her Florence speech mapping out her Brexit stance.

Theresa May spent 2018 getting her ducks in a row for her Withdrawal Agreement, which faced fierce opposition from both within the Conservative Party and from opposition parties in the Commons.

The European Research Group, which included the likes of Jacob Rees-Mogg and Mark Francois, believed Mrs May's deal left the UK too closely aligned with the EU, whereas many opposition parties thought it was too severe a departure.

By 14 November her Withdrawal Agreement was published - despite losing chief negotiator David Davis in July - which was endorsed by the European Union 11 days later.

But on the 15th, Dominic Raab also stepped down as Brexit Secretary, to be replaced by Stephen Barclay, after Mr Raab said the deal would be "damaging for the economy [and] devastating for public trust in our democracy."

Halfway through December, Mrs May announced the date for the first meaningful vote on her Brexit deal which would be held on 15 February, 2019.

This year has been defined by tensions over Brexit.

Three deadlines for leaving the EU have been missed (in March, April and October) and a number of "meaningful votes" and indicative votes have also failed to push through an agreed Brexit strategy.

In early May, the Lib Dems and the Green Party enjoyed significant boosts to their councillor numbers.

Later in the month, Nigel Farage's brand new Brexit Party tore up the form books by winning the European elections, leaving Theresa May's Tories in fifth place.

The following day, the Tory leader announced her resignation. She was replaced by Boris Johnson in July following a divisive, "blue-on-blue" leadership contest.

At the end of August, Mr Johnson prorogued Parliament in an attempt to push through his own version of Brexit, but a month later the Supreme Court ruled that prorogation unlawful in what was a groundbreaking case.

By October, the new prime minister had struck up a fresh Withdrawal Agreement with the European Union, but Parliament voted for more time to scrutinise the said deal.

As the UK hurtled towards "Brexit Day" on 31 October, without a Parliament-backed agreement, the EU opted to extend Article 50 to 31 January 2020.

On 29 October, a fourth general election of the decade was called and, eventually, agreed to be held on 12 December after some minor inter-party squabbling.

Boris Johnson won the Conservatives their biggest majority since 1987 after they ripped apart the "Red Wall" in Labour heartlands.

The election led to Jeremy Corbyn's announcement that he would not stand in another general election for Labour, and saw the rise and fall of Jo Swinson, who had only been appointed Lib Dem leader in July.

It also saw the SNP enjoy a strong resurgence, giving Nicola Sturgeon's independence argument new life.

2019 also saw John Bercow step down as Speaker of the House of Commons in November after a decade in the chair. He was replaced by Labour's Sir Lindsay Hoyle.

Although the last decade has been defined by division and instability, there is no reason why the 20s cannot offer hope, unity and joy.

Whether you voted to Leave or to Remain; whether you voted for the Conservatives, Labour, the Lib Dems, the SNP or anyone else; whether you're young or old, a boy or a girl, heterosexual or a member of the LGBTQ+ community, black, white or anything in between, we move into a new decade with renewed hope as a country.

Brexit is inevitable and should eventually provide clarity and stability; younger people are becoming increasingly involved in political causes; the environment has become an increasingly pressing issue that more and more people are getting behind; and as individuals, we remain free in a prosperous country.

So, we can wave goodbye to the 2010s that have given us, as journalists, an abundance of exciting and groundbreaking topics to write about, and we usher in a brand new decade that will no doubt give us plenty more.

Happy New Year everyone. And enjoy the brand new "Roaring Twenties".