Tonight with Andrew Marr 6pm - 7pm

8 March 2024, 16:54 | Updated: 8 March 2024, 23:09

The UK has earned second place for being the most miserable country in the world, a "worrying" new mental wellbeing report has found out.

With Covid and the cost-of-living crisis, it is more than understandable why struggling Brits are gloomy, with the UK just missing out on top spot for the most miserable.

The UK landed 70th out of 71 for overall mental wellbeing, earning an average score of 49, classifying the UK as enduring - comparatively low compared to the average global score of 65.

The report found that UK mental wellbeing levels in 2023 had not recovered from pre-pandemic levels, according to researchers at the US-based Sapien Labs think tank.

35 per cent of respondents in the UK said they were struggling with their wellbeing.

Read more: UK has second highest rate of cocaine use in the world, figures show

Overall, the highest proportion of people who said they were not coping lived in Britain, Brazil and South Africa.

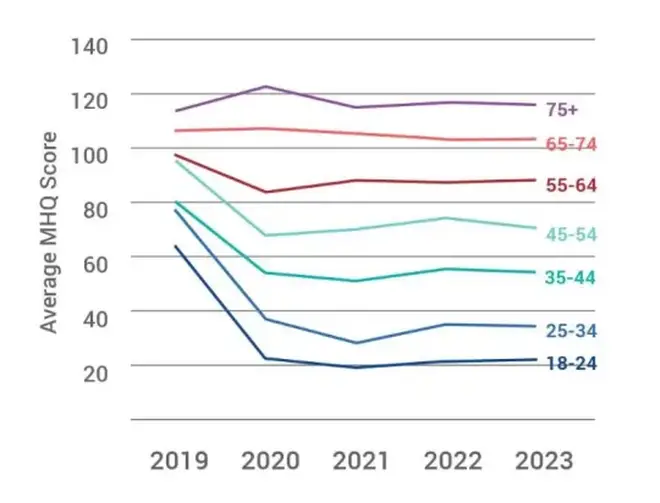

Whilst wellbeing for those over 65 has remained steady, 18-24-year olds across eight English-speaking countries' mental health has shown the least improvement since 2020.

Also struggling are young adults and poorer families who have endured two economic recessions in just four years, the cost of living crisis and rising rent and house prices.

Another issue making Brits miserable is the lack of trust for political leaders, such as chaos in Westminster, changing prime ministers and partygate.

Across all age groups, the study found that eating extra-processed goods results in much worse mental wellbeing.

60 to 70 per cent of food eaten in the UK is extra processed, with over half of Brits eating it daily reported feeling distressed, compared to 18 per cent who rarely or never do.

In the eight English-speaking countries tracked since 2019, the average Mental Health Quotient (MHQ) fell by 8% from 2019 and 2020.

On the other side of the globe, only 26 per cent of people in Tajikistan, Bangladesh and Syria said they were distressed or struggling.

Yemen scored better than the UK, Ireland, and Australia, scoring 59 for mental wellbeing - even though 21.6 million people need humanitarian assistance.

Countries that scored the highest for wellbeing include poorer countries in Africa and Latin America, as well as the Dominican Republic, Sri Lanka and Tanzania.

The number of people who said they were distressed or struggling increased from pre-pandemic years to 2023, and has shown little change for all 71 countries.

Conducting the study, scientists said: "Overall, the insights in this report paint a worrying picture of our post-pandemic prospects and we urgently need to better understand the drivers of our collective mental wellbeing such that we can align our ambitions and goals with the genuine prosperity of human beings."

Taking first place for the most miserable is Uzbekistan - a country situated in central Asia.

The UK government advises against travelling to Uzbekistan's border with Afghanistan, unless essential.

17 per cent or so who live there are under the poverty line, according to the Asian Development Bank.

Over half a million people across 71 countries responded, with experts finding that low scores for richer countries were down to early-age smartphone use, eating highly processed food and loneliness.

The study also focused on mood and outlook, motivation and drive, social self, adaptability and resilience, mind-body connection, and cognition.

Data was collected via the MHQ assessment, with scores ranging from -100-200.

Scores under zero represent distressed or struggling

Between zero and 50 meant enduring and 50-100 means managing,

Scores between 100 and 200 meant succeeding or thriving.

Dr Tara Thiagarajan, Sapien Labs Founder and chief scientist, the Daily Mail that there was a reporting bias as the survey was only open to people who had Internet access in each country

This meant that within a less developed country, people surveyed likely also were more well-off and educated, making them more similar to people in developed countries.